Juggling egos and rivalries, art and politics is all in a day's work for an A-list festival director. Moritz de Hadeln, former chief at Berlin and Venice, gives MELANIE RODIER a glimpse inside a job where a year's work is judged on two crucial weeks

When Mike Leigh picked up the Golden Lion for Vera Drake at the Venice film festival this year, his acceptance speech was laced with a barely concealed glee. "I'd like most sincerely to thank the Cannes film festival which rejected my film. Thank you Venice." Months earlier, Cannes had famously not selected Leigh's film, which went on to score near-universal critical acclaim and is now a front-runner for Oscar recognition.

Leigh later said. he had not meant to take a shot at Cannes, which did not offer a reason as to why his film had been rejected. "I can only reflect that my film wasn't good enough for Cannes," he says.

The brouhaha came hot on the heels of an earlier controversy, this time between Cannes and Berlin. The latter lost out on a competition screening of Walter Salles' The Motorcycle Diaries, which the former snagged from under its nose. "If a director cannot accept my invitation, one that he has had for three months, then I have to make my programme without him," said Berlinale artistic director Dieter Kosslick, somewhat snippily at the time.

Moritz de Hadeln sighs with resigned recognition. Nearly four decades as a top-flight festival chief have taught him that missing a potential hit is the bane of the job. "The strange thing about directing film festivals is that one needs nerves af steel to survive the unavoidable attacks from critics, and the sensitivity of a child to feel emotions when selecting films. Two things that contradict each other," he says.

"We cannot rely on reviews in Screen or Variety to know how the film will be received," says de Hadeln. "lt's left to our own judgement, to mine and that of my colleagues on the selection board, and one hopes that one has not made the wrong choice. It happens that in many cases I made the right choices after listening to my colleagues, and I'm very proud of it."

While every festival needs a figurehead who will take the praise as well as the flak in the industry's habitual festival post-mortems, the often irascible and always outspoken de Hadeln says that running a festival is all about teamwork.

"A festival director's main job is to animate, to motivate, a team. Because the event is so complex, so rich, and in the case of Berlin and Venice, so big, that one man alone cannot do much. If he does not have a team working for the same scope as he is, then he is lost."

"She pretended she had seen it before"

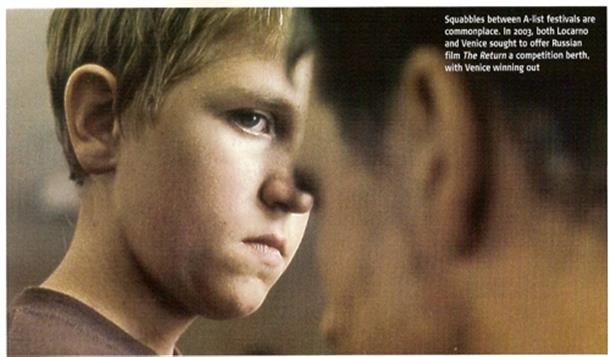

During his career, de Hadeln has switched between jobs in Locarno, Berlin and Venice. He says there is not much love lost between A-list festivals. One of the most high-profile examples of festival rivalry was when Venice and Locarno squabbled in 2003 over the competition programming of The Return, the debut of Russian director Andrei Zvyagintsev.

According to some reports, the film was offered to both festivals but was rejected by Venice's Critics' Week. Then, Locarno director Irene Bignardi announced the film would play in competition at the Swiss festival. The film's sales agent, Raissa Fomina of lntercinema Art Agency, confirmed it to Locarno and apparently informed Venice.

But the next day, Venice came back with an official invitation for the main competition. The film's producer, Dimitri Lesnevsky, told Fomina to cancel Locarno. By this point Bignardi had already unveiled The Return as part of her line-up, and sent a message to de Hadeln, suggesting there might have been a misunderstanding.

The picture went on to win the Golden Lion in Venice and de Hadeln recalls the Russian film's discovery as one of his greatest triumphs, disputing Locarno's claims that it was the first to accept the film.

"Irene Bignardi did ask for it, after we had accepted it, pretending that she had seen it before." He suggests. "The true fact is that the film was offered to five or six festivals simultaneously, and they were all waiting to see what the number one, Venice, would decide. From the moment we said yes, the film was no longer available for other festivals." For her part Bignardi believes there is an unspoken agreement between festivals whereby one will not take a film that has already been accepted by another.

De Hadeln insists A-list festivals never negociate with each other. "Festivals have relatively friendly relations between each other as far as common problems are concerned. But as soon as competition comes into their relationship, there are no negotiations. Besides, what would there be to negotiate? ‘Don't take this film, please give it to me?' This would be ridiculous. No-one would ever do that," he says.

"One needs nerves of steel to survive the unavoidable attacks from critics, and the sensitivity of a child to feel emotions when selecting films"

Moritz de Hadeln

"I have not always shown the films I have liked, but have been convinced it was right and proper for a film to be shown because it comes at the right moment and represents something new"

Moritz de Hadeln

November 26 December 2, 2004

Number 1478, page 16 & 18

INTERVIEW

MORITZ DE HADELN

De Hadeln, who curated the Berlin film festival between 1980 and 2001 before being controversially dumped, and then moved on to the Venice film festival for another two years, says he regrets rejecting three films during his time in Berlin.

One of those was Hector Babenco's Pixote. "It was a very violent film with a scene of a boy being raped in a prison. I had members of my board who were so violently against this film, that I had to say 'OK, we won't take it.' After that, it became a cult film," he says.

He also turned down Giuseppe Tornatore's Cinema Paradiso and Roberto Benigni's Life Is Beautiful. Both films were re-edited by Miramax after de Hadeln's committee rejected them. Both went on to win a slew of Oscars and are among the most successful non-English-language films of all time.

Still, de Hadeln admits that within a festival, a director does occasionally have to make compromises. During his last year on the Lido, much ruckus was caused in the Italian media by rumours that Venice was forced to include Aurelio Grimaldi's Rosa Funzeca in its programme, as the film's lead actor and producer, Ida Di Benedetto, was the lover of cultural minister Giuliano Urbani. Urbani refused to comment on press reports at the time, and Di Benedetto herself denied having anything other than a platonic relationship with the minister.

The Return, by Andrei Zvyagintsev

Page 1 of 2

Page 1 of 2